Vida de mujeres. Por Lot Winter

20 de abril 2022

A menudo me he enfrentado a la idea de que el feminismo ya no es necesario. Que las mujeres ya lo tenemos todo, y que no es necesario oponerse a más desigualdades en nuestra sociedad, porque ya no existen.

Estas confrontaciones me enfurecen, sobre todo porque vengo de las mismas tradiciones y patrones, y por lo tanto, es difícil señalar las áreas exactas, donde experimento la necesidad de un trato igualitario. Es simplemente invisible para mí, a menos que forme parte de las conversaciones tan importantes sobre el feminismo.

No se trata sólo de la igualdad salarial, de la educación o del derecho al voto, aunque esos derechos básicos todavía tienen un largo recorrido para muchas mujeres en todo el mundo.

También se trata de esas desigualdades invisibles a las que las mujeres se enfrentan a diario. El comportamiento tradicional se ha integrado a través de generaciones. Patrones de los que estamos cansadas, pero con los que seguimos lidiando, porque la sociedad sigue diciéndonos que ya lo tenemos todo, y que no podemos tener más.

De eso se trata este trabajo, no sólo de sacarlo a la luz para los demás, sino sobre todo para mí misma, ya que me he quedado sin argumentos demasiadas veces. Espero que estos visuales puedan convertirse en parte de los argumentos para otros, que los necesitan, como yo a veces. Ese es el humilde propósito de mi colección “Vida de Mujeres”

I’ve often been confronted with the idea, that feminism is no longer necessary. That we women have it all now, and there’s no need to oppose more inequality in our society, because it no longer exists.

These confrontations infuriate me - mostly, because I come from the very same traditions and patterns, and so, it’s difficult to pin out the exact areas, where I experience the need for equal treatment. It’s simply invisible to me unless I stay a part of the very important conversations about feminism.

It’s not only about equal pay, education, or the right to vote, although those basic rights still have a long way for many women around the world.

It’s also about those unseen inequalities, women face daily. Traditional behavior has been integrated through generations. Patterns that we’re tired of, but still deal with, because society continues to tell us that we have it all now, and we can’t have more.

That’s what this body of work is about - not only to bring it into the light for others but most of all myself, as I’ve run out of arguments too often. I hope these visuals can become a part of the arguments for others, that need them, as I sometimes do. That’s the humble purpose of my collection “Vida de Mujeres”.

¿Puedes dejar de quejarte? Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm -Can You Stop Mansplaining? Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

El término “machoexplicacion” se inspiró en un ensayo, "Men Explain Things to Me: Facts Didn't Get in Their Way", escrito por Rebecca Solnit. En el ensayo, Solnit contó una anécdota sobre un hombre en una fiesta que dijo que había oído que ella había escrito algunos libros. Ella empezó a hablar de su más reciente, sobre Eadweard Muybridge, y el hombre la interrumpió y le preguntó si había "oído hablar del importantísimo libro de Muybridge que se ha publicado este año", sin considerar que podría ser (como de hecho era) el libro de Solnit. Solnit no utilizó la palabra mansplaining en el ensayo, pero describió el fenómeno como "algo que toda mujer conoce". ¿A quién le gusta ser interrumpido?

The term mansplaining was inspired by an essay, "Men Explain Things to Me: Facts Didn't Get in Their Way", written by Rebecca Solnit. In the essay, Solnit told an anecdote about a man at a party who said he had heard she had written some books. She began to talk about her most recent, on Eadweard Muybridge, whereupon the man cut her off and asked if she had "heard about the very important Muybridge book that came out this year"—not considering that it might be (as, in fact, it was) Solnit's book. Solnit did not use the word mansplaining in the essay, but she described the phenomenon as "something every woman knows”. Who enjoyed being cut off?

Deten los silbidos Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Stop the Catcalling Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Lo creas o no, es posible no llamar la atención a una mujer por su aspecto. Es posible que el primer cumplido no se refiera a su figura o a lo que te atrae sexualmente. Es posible verla como una persona y no como algo que hay que saltar. ¿No crees que podríamos mirar a las mujeres como personas y no como objetos?

Believe it or not, it is possible to not call out a woman for her appearance. It is possible that the first compliment is not about her figure or whatever you’re sexually attracted to. It is possible to see her as a person rather than something to jump. Don’t you think we could look at women as people and not objects?

No quiero esperar Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - I Don’t Wanna Wait Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Estoy harta de esperar a que se solucionen las cosas. Que se conformen con un ritmo más lento y se ajusten y acepten el statu quo. Déjenme mover las cosas, no somos sólo máquinas de sí. Somos seres humanos con ideas y ganas de vivir. ¿Por qué esperamos a que los demás nos vean cómo somos?

I’m so done waiting for them to figure things out. To settle for a slower pace and adjust and accept the status quo. Let me move things, we’re not just yes machines. We’re human beings with ideas and lust for life’s pleasure. Why are we waiting for the others to see us as we are?

No bailo para ti Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - I’m Not Dancing for You Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Tal vez estoy aquí por el placer de hacerlo. Tal vez me gusta bailar por mi cuenta, tal vez me siento más libre. Puedes mirar todo lo que quieras, pero no asumas que esto es para ti. ¿Has pensado que, aunque lo hagas por una recompensa que puede venir después, nosotros no lo hacemos?

Maybe I’m just here for the pleasure of it. Maybe I like dancing on my own - maybe it feels freer. You can watch all you want, but don’t assume any of this is for you. Have you thought, that though you may do it for a reward may come afterward, we don’t?

No soy tu esclava. Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - I’m Not Your Slave. Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Es hora de desencadenar. Es hora de ir libremente sin supervisión. De viajar, caminar y tener sexo como los hombres pueden hacerlo. Es hora de pasar por debajo del radar y simplemente ser. ¿Quién disfruta de la persuasión de todos modos?

It’s time to unchain. It’s time to go freely without supervision. To travel, walk and sex like men can do. Time to go under the radar and just be. Whoever enjoyed persuasion anyway?

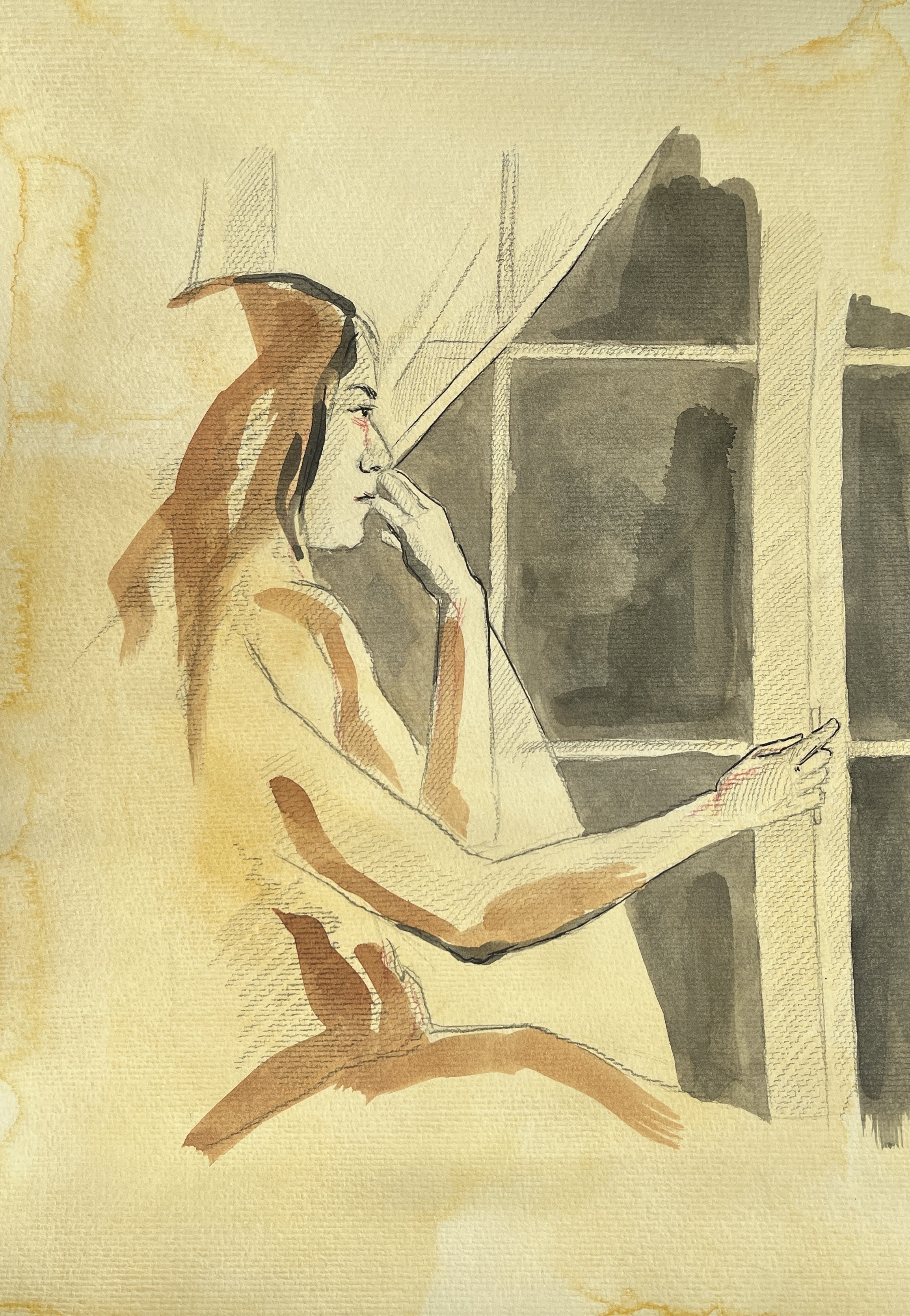

Déjame ser mi propia musa Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Let Me Be My Own Muse Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

A mí también me gusta mi cuerpo. Yo también quiero retratarlo, pero dejad que os lo muestre a través de mis ojos. Es hora de que el mundo vea que no somos objetos, ni sólo musas, que somos seres humanos expresivos. Hemos pasado décadas y siglos posando para los varones, los intelectuales asignados en la sociedad. Ahora, el mundo arde por el poder una vez que mostramos los aspectos de la belleza y el poder femenino de la forma en que siempre los hemos sentido. ¿Quién mejor que nosotras para contar nuestras historias?

I too like my body. I too want to portray it - but let me show you through my eyes. It’s time for the world to see that we’re not objects - nor just muses, that we’re expressive human beings. We’ve spent decades and centuries posing for the males, the assigned intellectuals in society. Now, you’re seeing a world on fire over the power once we show you the aspects of feminine beauty and power the way we’ve always felt it. Who would be better to tell our stories than us?

Deja de seguirme Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Stop Following Me Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Sólo las personas que se identifican como mujeres pueden relacionarse. El mismo escenario puede parecer muy diferente si estás sola o con gente. Con gente, estás a salvo. Sola, eres un objetivo potencial. Estamos preparados con las llaves, tenemos el teléfono en marcación rápida, fingimos estar hablando con gente por teléfono y tratamos de parecer menos atractivas; a veces esto último es lo que más nos salva. Envíame un mensaje de texto cuando estés en casa y ponlo en localización directa. ¿Por qué seguimos necesitando estar acompañados de una manera u otra, para estar seguros?

Only people who identify as women can relate. The same scenario can look very different whether you’re alone or with people. With people, you’re safe. Alone, you’re a potential target. We’re ready with keys, we have the phone on speed dial, pretend to be talking to people on the phone, and try to look less attractive - sometimes the last one is the biggest saver. Text me, when you’re home and put it on live location. Why do we still need to be accompanied one way or the other, to be safe?

Deja de tocarme Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Stop Touching Me Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Está en todas partes: en las multitudes, en los bares, incluso en el lugar de trabajo. Suele estar relacionado con una situación en la que el que toca parece querer proteger o ayudar. En la multitud, puede ser una mano en la cintura si se están acercando a la mujer o incluso sólo quieren atravesar la multitud, pero nunca harían algo así a un hombre. En el lugar de trabajo, cuando la persona que toca está ayudando en algo, ¿cuándo ha pasado a ser aceptable tocar sin consentimiento? ¿Por qué hay formas diferentes de tocar a las mujeres que a los hombres?

It’s everywhere - in crowds, in bars, even in the workplace. Usually connected to a situation, where the toucher seems to want to protect or help. In the crowd, it can be a hand on the waist if they’re approaching the woman or even just want to get through the crowd, but they would never do such a thing to a man. In the workplace when the toucher is helping out with something - when did it ever become okay to touch without consent? Why are there different ways of touching women than men?

¿Por qué tengo que equilibrar el trabajo y la vida? Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Why Do I Have To Balance Work and Life? Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

Él es el héroe si lleva al bebé de paseo, cambia los pañales o incluso cuida del niño mientras trabaja. Él es un héroe, y ella es la madre. El bebé es una extensión de ella, se espera que sea la principal cuidadora en todo momento. Difícilmente podría ser un héroe porque sólo es una madre. Si actúa como el padre, estaría descuidando a su bebé, sería una mala madre. Cuando las mujeres empezaron a trabajar, decía mi abuela, tuvimos dos trabajos. ¿Por qué a las mujeres se les pregunta a menudo cómo concilian la vida laboral y familiar? ¿Por qué a los hombres no se les hace la misma pregunta?

He’s the hero if he takes the baby for a stroll, changes diapers, or even takes care of the kid while working. He’s a hero, and she’s the mom. The baby is an extension of her, she’s expected to be the main caretaker through all times. She could hardly be a hero because she’s just a mom. If she acts as the father, she’d be neglecting her baby, she’d be a bad mom. When women started working, my grandmother said, we got two jobs. Why is it women are often asked, how they balance work and family life? Why are the men not asked the very same question?

¿Me tomarías en serio con ropa de mujer? Técnica mixta sobre papel, 30 x 21 cm - Would You Take Me Seriously In Women’s Clothes? Mixed media on paper, 30 x 21 cm

El traje de mujer se popularizó en los años 80, cuando se lanzó la píldora anticonceptiva y, de repente, muchas más mujeres podían trabajar (piénsalo). Teníamos que parecernos a los hombres, vestirnos como ellos, pero de forma femenina. Hoy en día, tenemos que reprimir las emociones para parecer profesionales, o ser emocionales de forma masculina, como la ira, pero no demasiado, porque puede parecer fácilmente histérica viniendo de una mujer. No podemos vestirnos demasiado femeninas con vestidos o faldas, porque no parece serio como el traje. Debemos encajar o salir. ¿Cuándo se ha relacionado el talento y las habilidades con la forma de vestir?

The women’s suit grew popular in the 80s when the contraception pill was released and suddenly, a lot more women could work (think about that one). We had to look like men, dress like them, yet in a feminine way. Nowadays, we have to suppress emotions to look professional, or be emotional in a masculine way such as anger, but not too much, because it can easily seem hysterical coming from a woman. We can’t dress to feminine with dresses or skirts, because it doesn’t appear serious like the suit. We must fit in or get out. When was talent and skills ever connected to how we dressed?

Biografía de la artista

Soy un artista visual danésa y trabajo con una mezcla de abstracto y figurativo. Aprovecho absolutamente la autenticidad los momentos verdaderos y emocionales que atravesamos como seres humanos. Mi formación académica consiste en diseño y emprendimiento, y por esa razón, comencé mi carrera artística desde una mentalidad emprendedora. Actualmente estoy estudiando en el Instituto de Arte de Milán.

Biography of the artist

Soy un artista visual danésa y trabajo con una mezcla de abstracto y figurativo. Aprovecho absolutamente la autenticidad los momentos verdaderos y emocionales que atravesamos como seres humanos. Mi formación académica consiste en diseño y emprendimiento, y por esa razón, comencé mi carrera artística desde una mentalidad emprendedora. Actualmente estoy estudiando en el Instituto de Arte de Milán.